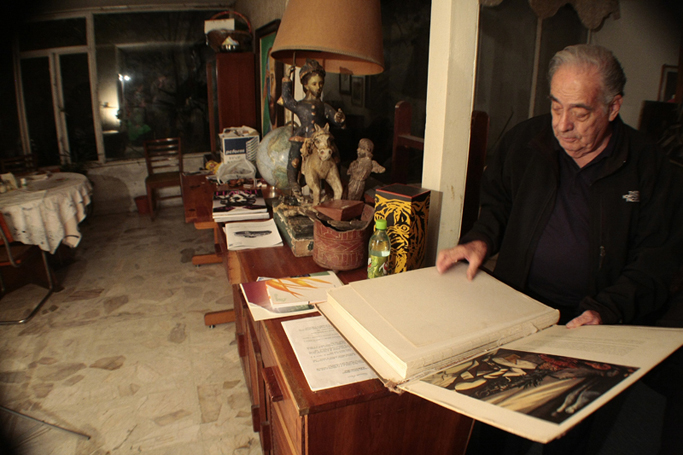

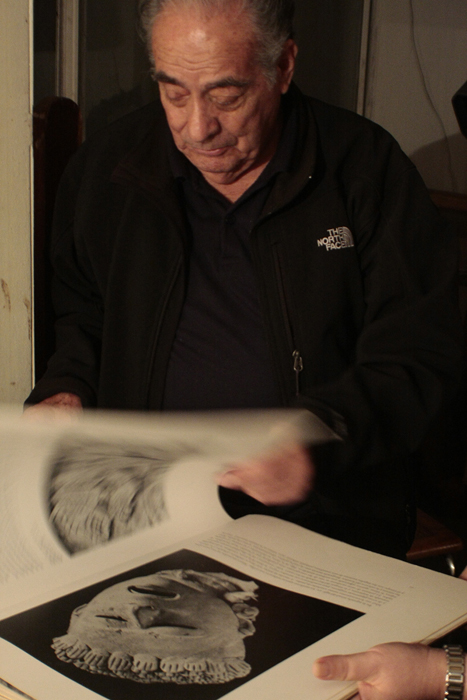

Clemente Orozco

FLAUNT MAGAZINE

Writen by Ingrid Barajas

Photography by Alex Gallo

Guadalajara

Flaunt: What is your relationship to your father’s art?

Clemente Orozco: I have what the Italians call senso sentico, which means a deep feeling for art. So, though my background is in science, I left my professional life as a chemist. I wanted to be a researcher. I devoted my whole life practically—it’s now about over 50 years—to my father’s work. I have become an authority as the curator and an expert in his works. As a matter of fact, I have written books. I’ve written more than a dozen, but only six of them have been published.

What do you feel his work did for Mexican identity?

That question is hard to answer. I don’t think he has done anything for Mexican identity. My father belongs in a very special category. His works are of universal meaning. Actually, he has not been understood by the Mexican public, because there is no real introduction to art [in Mexico]. There’s a complete confusion on what is art, what is ornamental art, and what is the difference between art and artisanal things.

In what contributions do you feel he made for the Mexican muralist movement?

I hope one day they will understand that [his is] the only work in this world that belongs in the category of monumental art. So, because he was a contemporary artist, he brought many innovations. One is that his work is completely devoid of any metaphysical representation. He also liberated the figures of any description. What he did was suggest the action. They carry a deep dimension of philosophical ideas: the man of the past, of the present and future.

Did you ever talk politics with him?

No. He went to the essence. For instance, that mural in the Palace of Fine Arts, it’s probably a pretext to that fabulous nude, the symbol of prostitution. But there is a universal prostitution in every field, not only politics, but [in] religious and social matters. Man behaves that way. As soon as he has power, he becomes alien; he goes by wind, not by reason. We never discussed—he left his images, and that’s it.

Did you learn about Mexican culture, history, and identity from your father?

He left some text in which he discusses history the way it took place. He was more the human being, and not a particular group. He opposed the Department of Indigenous Affairs. He said it is like a department of devils. Men should be treated as men, anywhere in this world, and be given the opportunity to learn, to understand, and the right to live.

Do you remember any words of wisdom he would share with you?

He was full of humor. He says, ‘If there is no humor there is no art.’ He took a particular gender, let’s call it, in between the romantic and the tragic, because man goes from both. Because if you think about these things, it’s quite tragic, and on the other side, it’s completely laughable. So between those extremes, he left those in his canvas.

How would you like future generations to think about his work?

He would say, whenever he was questioned, ‘I’m a painter.’ I would like to see him as a unique painter of monumental scale. He also used to say, ‘If these pictures have any meaning in five thousand years, it will not be because of subject matter. It will be because they are well done.’ It’s a message I would like to transmit. Unfortunately, he has been part of a myth—‘painter of a revolution’ or some such thing—which had absolutely nothing to do with him. He’s completely alone in the [monumental] category. He was able to give brush strokes twelve feet apart. He could paint at that scale. He produced 36 square meters in eight hours.

Eight hours?

Eight hours, yes. It was amazing. This painting, for instance, [Points] probably took him no more than two hours to paint.

Did he listen to music while he was painting?

Silence. Actually, when he was drawing he didn’t let anyone come to his studio, and [only] in very rare occasions he would let me in, because he needed something. No, he used to say that life is created in silence and seclusion, especially because he needed that time to think, and he didn’t want to be disturbed by anything. The walls in his studio didn’t have anything; they were white walls. He didn’t have anything hanging, so he was like he went into an altered state of mind.

Meditation?

[He was] completely taken and absorbed in his imagination. And he was able to bring it down to the paper or to the canvas or whatever the medium was.

What is your favorite work and why?

Because it is in one isolated space, Hospicio Cabanas [has] one of the six sets of murals. One can see the whole in a unit. You have knaves, you have cupolas, and you have walls. People don’t realize that’s what keeps it together from the aesthetic point of view, as well as a concept. The origin and the man is introduced on one panel and there is not even a man painted there, but it is the impetus of going to the unknown. You only see two caravels going into the ocean propelled by a huge wave, and it could be the man going to the cosmos. There is not even a man painted there.

How much impact did the Mexican Revolution have on your life?

Absolutely none. On the contrary, I think that the Mexican Revolution did the opposite and brought Mexico backwards.

For more information email us at rrppmedia@212productions.tv

Copyright © 2000 - 2011 | 212 Productions | GBA Productions S.A. de C.V. All Rights Reserved